The HMHS Britannic, the sister ship of the infamous RMS Titanic, was one of the most luxurious and awe-inspiring ocean liners of its time. Built as part of the Olympic-class trio by the White Star Line, the Britannic was intended to carry passengers and cargo across the Atlantic, similar to her elder sister. However, the Britannic’s fate would be tragically different from that of the Titanic.

This article explores the fascinating history, construction, brief career, and tragic sinking of the HMHS Britannic.

Table of Contents

The Birth of a Giant

Construction of the Britannic commenced in 1911 at the Harland and Wolff shipyards in Belfast, Northern Ireland. She was the third and final ship in the Olympic-class, following the Olympic and Titanic. Her construction employed some of the most advanced shipbuilding techniques of the time, including the use of over three million rivets to hold her massive steel hull together.

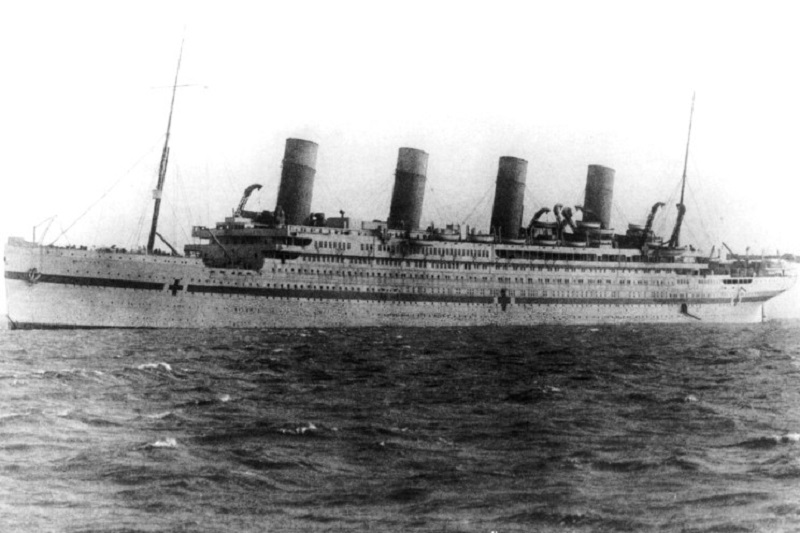

The Britannic’s design closely mirrored that of her sister ships, but with several modifications intended to improve safety. These alterations included a double hull and an increased number of lifeboats. The ship’s sheer size and luxurious amenities made her one of the most desirable ocean liners for passengers seeking a comfortable and grand journey.

Characteristics

The original dimensions of Britannic were similar to those of her older sisters of the Olympic-class, but her dimensions were altered while still on the building stocks after the loss of her older sister-ship Titanic. With a gross tonnage of 48,158, she surpassed her older sister-ships in terms of internal volume.

The Olympic-class ships were propelled by a combined system of two triple-expansion steam engines which powered the three-bladed outboard wing propellers whilst a low-pressure steam turbine used steam exhausted from the two reciprocating engines to power the central four-bladed propeller giving a maximum speed of 23 knots.

From Ocean Liner to Hospital Ship

Before the Britannic could embark on her intended commercial voyages, World War I erupted in 1914, and the ship was requisitioned by the British Admiralty to serve as a hospital ship and was prepared for emergency entrance into service with as little as four weeks’ notice.

Several of Liverpool’s large liners were converted for use as hospital ships, including Britannic, Aquitania, and Mauretania. Hospital facilities were constructed on board so they could provide medical services near the battlefields and transport the more severely wounded back to Britain.

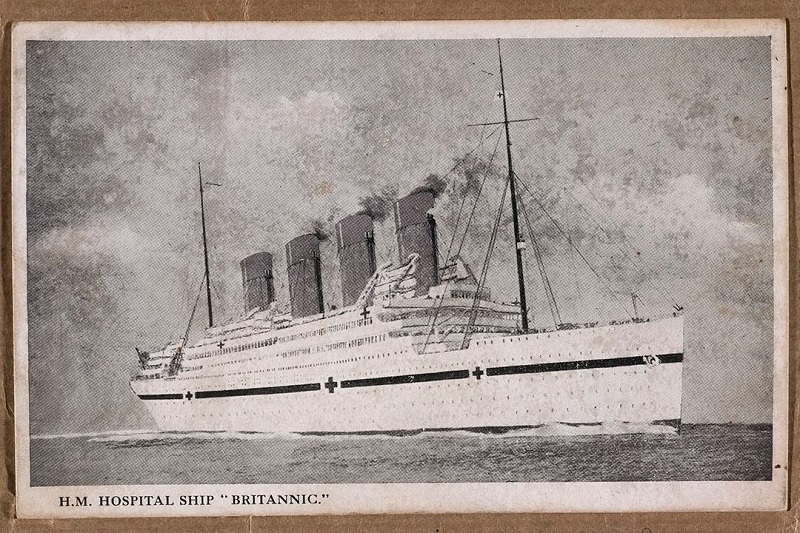

Britannic was repainted white with large red crosses and a horizontal green stripe and was renamed HMHS (His Majesty’s Hospital Ship) Britannic. In the interior of the ship, 3,309 beds and several operating rooms were installed. The common areas of the upper decks were transformed into rooms for the wounded. The cabins of B Deck were retrofitted to house doctors. The first-class dining room and the first-class reception room on D Deck were transformed into operating rooms for the wounded soldiers. The lower bridge was used to accommodate the lightly wounded servicemen.

During her time as a hospital ship, the Britannic carried out several successful missions, ferrying the wounded from various war zones. However, her days as a hospital ship were numbered.

The Hague Convention of 1907 stipulated that hospital ships would be granted immunity from enemy attack. They were painted white with a green horizontal stripe and red crosses to ensure they were easily recognized. Despite this, several hospital ships struck mines or were torpedoed and, when Germany declared unrestricted warfare in 1917, many of these vessels were targeted. Women serving as nurses found themselves on the frontline for the first time.

One such nurse was Florence Irving, a district nurse and midwife who enlisted for service with the Red Cross at the outbreak of war in 1914. She treated wounded soldiers on board Britannic and was on the ship when it sank. Florence survived and went on to treat patients at field hospitals in France. She was later decorated for her wartime service.

The Tragic Sinking of HMHS Britannic

On the morning of November 21, 1916, tragedy struck the Britannic. While transiting the Kea Channel in the Aegean Sea, the ship encountered a naval mine laid by a German submarine. The mine detonated, causing a massive explosion on the starboard side of the vessel.

The Britannic’s safety features, including the double hull and increased number of lifeboats, proved to be instrumental in minimizing the loss of life. Nevertheless, the ship’s fate was sealed, and within a matter of minutes, she started to sink.

Heroism and Tragedy in the Aftermath

In the midst of chaos, the crew and medical staff onboard acted swiftly to save as many lives as possible. Many showed incredible heroism, even sacrificing their own lives to aid others. Captain Charles Bartlett, who had previously served on the Titanic, was praised for his efforts to evacuate passengers and crew.

Despite the heroic efforts, 30 lives were tragically lost in the sinking of the Britannic. In total, out of the 1,066 people on board, 1,036 people survived the sinking. The ship’s rapid descent to the seabed left many questions and theories about what went wrong. Investigations were carried out to determine the cause of the disaster, and the findings shed light on the Britannic’s tragic fate.

Compared to Titanic, the rescue of Britannic was facilitated by three factors: The temperature was higher (68 °F (20 °C) compared to 28 °F (−2 °C) for Titanic), more lifeboats were available of which 35 were successfully launched and stayed afloat compared to Titanic’s 20 lifeboats. Help was closer and it arrived less than two hours after the first distress call compared to the three and a half hours for Titanic.

Investigations and Findings

The investigations into the sinking of the Britannic revealed that the naval mine explosion was the primary cause of the disaster. However, other contributing factors came to light during the inquiries. One notable issue was the failure to close the watertight doors adequately, which accelerated flooding and made it more challenging to control the ship’s sinking.

Additionally, there were debates about whether the Britannic should have been sailing at a higher speed through the dangerous waters, as excessive speed could have reduced the ship’s maneuverability and increased the damage caused by the explosion.

Initial planning and novelties

The plan of Britannic showed that she was intended to be more luxurious than her sister ships in order to compete with other ocean liners. More cabins were provided for passengers and were divided into three classes. The number of crew planned was increased from about 860 – 880 onboard Olympic and Titanic to 950 aboard the younger sister-ship Britannic.

Having in mind that children began to appear as part of the clientele that needed to be satisfied, a playroom for them was built on the boat deck. The A Deck of the ship was devoted in its entirety to the First Class, being fitted with a salon, two veranda cafes, a smoking room and a reading room. The B Deck included a hair salon, post office, and redesigned deluxe Parlour Suites. The most important addition was that of individual bathrooms in almost every First Class cabin, which would have been a first on an ocean liner. Aboard the Olympic and Titanic, most passengers had to use public bathrooms.

These facilities were installed but were soon removed because the ship was converted to a hospital ship and were never re-installed because the ship sank before she could enter transatlantic service, so the planned facilities were either cancelled, destroyed, reused on other vessels, like the Olympic or Majestic, or just never used. Of these accessories, only a large staircase and a children’s playroom remained installed.

Legacy and Influence

The sinking of the Britannic marked the end of an era for the Olympic-class liners. Despite her short-lived career, the Britannic’s tragic fate further highlighted the need for improved safety measures in maritime transportation. Her sister ship, the Titanic, had already emphasized the importance of sufficient lifeboats and other safety precautions, but the Britannic’s sinking reinforced the urgency for stricter regulations and practices.

After Germany capitulated at the end of the First World War followed, Germany agreed to hand over some of its ocean liners as war reparations, two of which were given to the company. The first, the Bismarck, renamed Majestic, replaced the Britannic. The second ocean liner, the Columbus, renamed the Homeric, compensated for other ships lost in the conflict.

The legacy of the Britannic also lives on through numerous books, documentaries, and films that recount her story. The ship’s sinking remains a captivating subject for historians and maritime enthusiasts, offering valuable lessons about the perils of the sea and the importance of safety in ocean travel.

Conclusion

The HMHS Britannic, the sister ship of the Titanic, played a significant role in maritime history. Built as an elegant ocean liner, she was tragically repurposed as a hospital ship during World War I. Her sinking following a naval mine explosion in 1916 further cemented the lessons learned from the Titanic disaster. The Britannic’s legacy reminds us of the importance of safety at sea and continues to captivate the imagination of people worldwide.

Read more posts on Science.

Leave a Reply